Can Virtual Reality Teach Clinicians of the Future?

Published July 15, 2022

By: Gabriel Perna

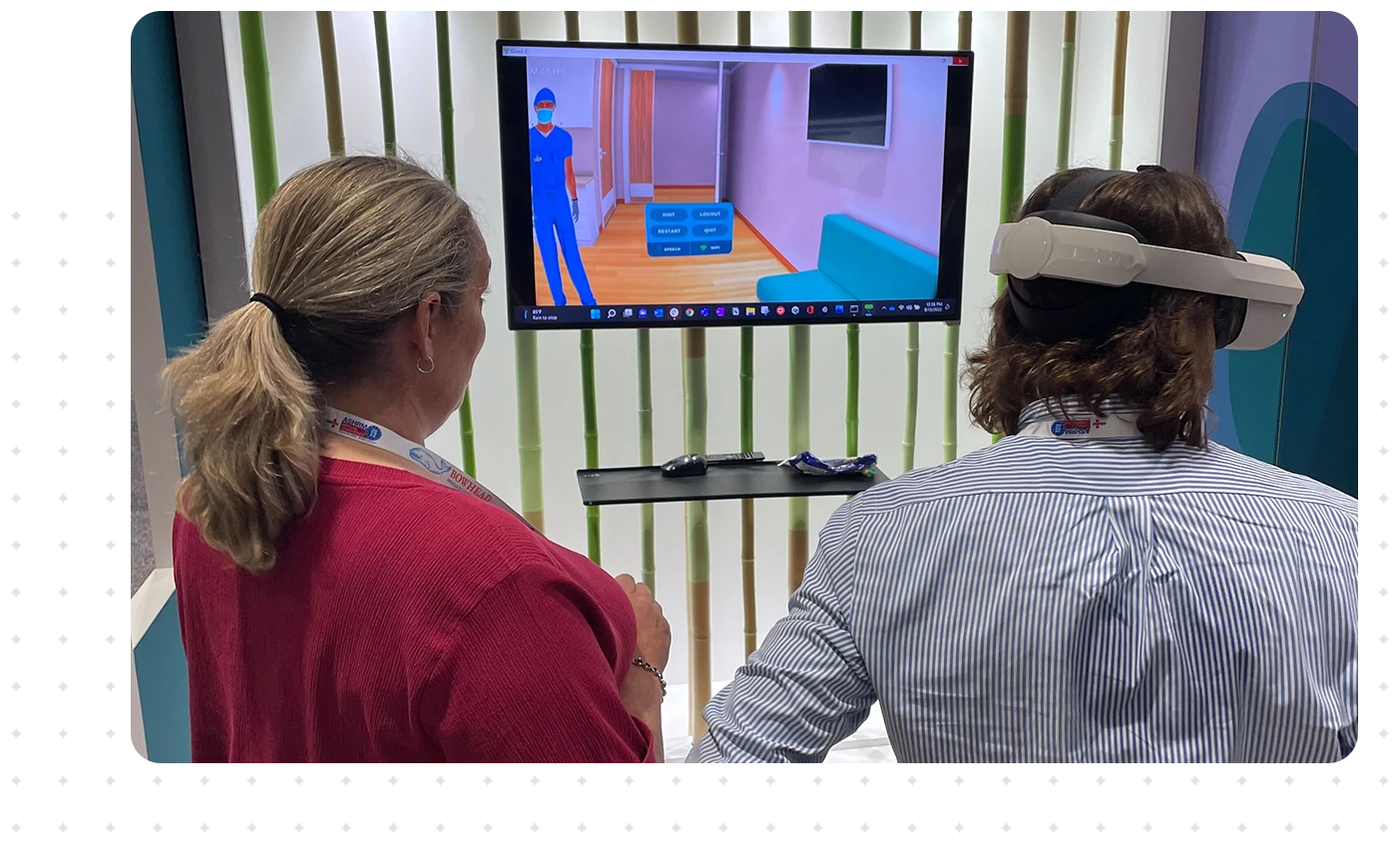

Health systems are increasingly using virtual reality to make medical training more efficient and cost effective.

“Virtual reality is a three-dimensional interactive experience, which means it is a better way to train than just looking at a cadaver and it’s less expensive too,” said Dr. Walter Greenleaf, the virtual reality/augmented reality expert at Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab.

Greenleaf has studied, developed and used VR systems in medicine for more than 30 years. He said the technology has evolved making it more cost effective for health systems to adopt. Developers can program faster and more realistic spatial awareness of objects, he said. Plus, headsets are lighter and less cumbersome to use.

The advancement of this technology has made the cost more affordable compared to in-person training exercises. According to a study in the Journal of Medical Internet Research from researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, using virtual reality to train clinicians on cardiac arrest events was 83% less expensive than in-person simulation.

“To train a surgeon in virtual reality is a fraction of the cost of cadaver-based training that we do in person,” said Dr. Cory Calendine, an orthopedic surgeon at the Franklin-based Bone and Joint Institute of Tennessee.

Calendine, who uses VR to instruct residents, said it’s easier to train people because providers don’t have to arrange for everyone to be in the same location. All collaboration can be done virtually and at the provider’s convenience.

“If you can train them in the virtual space on their time, not during a procedure, and allow them to do this in a more efficient way, it’s a powerful thing,” Calendine said.

Sign up for Digital Health Business & Technology’s newsletters to stay informed on industry trends

The numerous uses of VR in medicine

Efficiency and cost are two reasons why NYC Health + Hospitals announced last Thursday it was rolling out VR systems to help train obstetricians across its 11-hospital system. Dr. Wendy Wilcox, NYC Health + Hospitals’ chief women’s health service officer, said the VR system will allow the system to rely less on traditional methods of simulation, which are time-consuming, require onsite visits and advance scheduling.

“Virtual reality can really increase our capacity in training,” Wilcox said. “If you can get a realistic training course into the hands of the provider that they can access whenever they want, it can be cost effective.”

A study, published in Computers, Informatics, Nursing, found that while VR was more expensive to install in the first year of using it to train hospital workers, it ended up being cheaper over a three-year period than live exercises. The cost of the live exercises remained fixed, while the VR training costs went down once it was in place.

Beyond the advantages of efficiency and cost, one of VR’s major appeals is it can be used across a variety of scenarios. Greenleaf said it can teach both clinical and soft skills, which is harder to get from a traditional training situation.

“If you’re looking at a PowerPoint slide or reading a book and trying to understand what it’s like to be a patient, especially when there’s a cultural, age or gender gap, it can be hard to learn how to establish rapport with a patient,” Greenleaf said. “With VR, we can practice and learn those skills.”

Vanderbilt’s School of Nursing completed a $23.6 million expansion in 2019 that included the creation of a simulation lab. As part of this lab, Vanderbilt has tested virtual reality across a variety of applications, including usage of ultrasound equipment, empathy training and exploring ways to reduce stress in the workplace.

Dr. Patricia Sengstack, the school’s senior associate dean for nursing informatics, is bullish on virtual reality because of its potential.

“The concept of virtual reality and immersing someone in that kind of environment, there are a lot of different applications for that,” Sengstack said. “Not just in academia with training students, but in the real world over on the medical center side when nurses need to refresh their education every year. I think it will just continue to expand.”

Barriers

But not everyone is on board with virtual reality. Dr. José Barral, chair of biomedical science at Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine in Pasadena, California, prefers the usage of augmented reality to virtual reality when training medical students.

Kaiser Permanente is opening a new Anatomy Resource Center (ARC), which will use emerging technologies to train students on anatomy rather than relying on cadavers. Barral said augmented reality, which is a partially immersive experience rather than a fully one, was better received.

“For virtual reality, many people experience discomfort when wearing the device,” Barral said. “Augmented reality is better because it gives your brain a grounding. You don’t lose the ground floor. You don’t lose the walls. You still see the objects around you, you just have the augmented projection.”

For nursing students at Vanderbilt, motion sickness was the biggest downsides to the VR technology, said Kelly Aldrich, director of innovation at the school.

“You put this headset on, it’s 360 degrees every angle you look,” Aldrich said. “It can get you if you’re prone to motion sickness. I think that’s something for the tech industry to advance on.”

Another barrier is the lack of cross-platform standards, Greenleaf said. There are emerging VR platforms in many specialties—oncology, obstetrics, orthopedic surgery and behavioral medicine, to name a few—but there isn’t yet cross-functional capacity. This means health systems would have to invest in multiple VR systems for training purposes, which would be costly.

Greenleaf also said the perception of VR in medicine is that it’s more science fiction rather than a legitimate training tool. He said a cultural shift is needed for VR to make more headway across the healthcare industry.

“I think there’s going to be a new generation of diagnostics, training tools and interventions, but people don’t quite appreciate that yet,” Greenleaf said. “They still view it as something exotic and bizarre.”

Calendine echoed this sentiment.

“A lot of the barriers are just regarding the concept itself,” he said. “It’s new and different. We need to better articulate what the value is and how it can help.”